Abstract

This paper comparatively analyzes how the government

owned main stream media and private owned main stream media approached and

reported the Madhesha Movement 2007. The conclusions of the paper are (i)

government media reports events along the line of the ruling government and,

(ii) private media are quick to understand the popular sentiment and report

events that is sellable and liked my most of the public.

Introduction

Terai is one of the four geo-ecological

zones lying in the southern part of Nepal. It is a plains region that occupies

about 23 percent of the land but over 50.27 percent of the population lives

here (CBS, 2012). Among the Nepalese living in Terai[1] 64.22 percent are the Terai’s

original inhabitants while 35.78 are hill migrants, also called Pahadhis (Rimal,

2009, p. 13). The Madheshis claim that the Terai’s upper caste, Terai Dalits,

Tharus and Terai Mushlims are all Madheshis (Mathema, 2011, p.2). However,

Tharus, some Terai Dalits and Terai Mushlims claim that they are not Madheshis;

the undisputed Madheshis are the Terai caste group and Dalit who make up 37.89

percent of the Terai’s population (ibid.).

Despite of their significant presence in

Terai, Madheshi community have long been marginalized by the state when it

comes to issues like citizenship, employment opportunities, political

participation, social recognition, etc. According to Cheah (2008), Madheshis

have been treated unfairly and denied rights as citizens of Nepal throughout

the history of Nepal. Mathema (2011) explains that the missing history of Terai

has also contributed to marginalization of Madheshis because most of the people

in Nepal think that the Madheshis are either Indians who migrated to Nepal or

they are descendents of Indian migrants sent to Nepal to strengthen the

cultural domination of India (p.44). The

Dhoti-Kurtha, the traditional dress of Madheshis, never being reconginzed as a

proper formal dress for a Nepali even by the post-1990 democratic government is

the symbol of the unexceptance of their culture by the state (p.50). Despite

the Jana Andolan in 1990, aristocracy continued to control national politics

and state affairs; governments of Nepal failed to ensure power-sharing and an equal

distribution of resources among Madheshis, Janajatis, women, dalits and other

indigenous nationalities living in the Terai (Cheah, 2008). High castes of hill

communities continued to dominate the highest appointments in civil service and

government offices (ibid.). Similarly, Nepali language being official language

and the the sole language to be used as medium of instruction in education

throughout Nepal has hampered many Madheshis to pass exams and thus made them

not eligible to fight for the government jobs (p.52). This is how state seem to have intentionally

marginalized Madhesha from main stream politics and development as well.

But the Madheshi

movement of 2007 which took place after the overthrow of monarchy and the

restoration of democracy shook the Nepali state. The government employed

security forces to try to control the situation and stop the uprising but they

proved ineffective. Within a week the protests developed into a mass movement,

the ferocity of which was such that it forced the government to amned the

interim constitution to accommodate the demands of the agitating Madheshis.

Madheshi Movement: Historical Overview

After Ranas were overthrown in 1951, Nepal

became a democratic country with a ceremonial monarchy. However, according to

Gaige (1975), some Terai elites who helped the political parties to overthrow

the Ranas felt excluded from national politics and formed a Terai-centered regionalist

political party in 1951, collecting elites of Terai in the name of Nepal Terai

Congress (NTC), whose main political demand was to create an autonomous Terai

within Nepal and to increase the presence of Madheshis in the civil service (as

qtd in Mathema, 2011, p. 5). But the

failure of NTC to win any seat in the election of 1959 was a major blow to the

party causing to it’s gradually disintegration (p.6).

Kulananda Jha and Baldeva Das of the NTC

are the ones who established Madhesha issues in the main stream of Nepalese

politics (Yadav, 2008, p. 76). Gajendra Narayan Singh of Nepal Sadbhawana Party

(NSP) is also one of the prominent Madheshi activists who built on the Madhesh

issues established by NTC (Mathema, 2011, p. 7). During the Panchayat era

(1960-1990) when it was illegal to register a political party, Gajendra Narayan

Singh formed a cultural organization in the name of Nepal Sadhavawana Parisad[2] that campaigned for greater

cultural rights for Madheshis (ibid.). However, in the parliamentary election,

followed by the restoration of democracy in 1990, NSP did not get much support

from the Madheshi community for whom they claimed they were fighting; the party

could only won six, three and five seats in the elections of 1991, 1994 and

1999 respectively (ibid.).

Maoist Movement and Madhesha

Till 1999, NSP was the only political

party in Nepal that claimed to be fighting for the Madhesha issues. But in the year

2000, the Maoists established various central-level ethnic[3] fronts including the Madheshi

Rashtriya Mukti Morcha (MRMM) (Mathema, 2011, p. 8). MRMM was described as a

wing based on Madhesha and had promised for federal state in Madhesh, rights of

self determination and many other assurances during their revolution against

the monarchy and the state (Shah, n.d.). Establishment of MRMM end the monopoly

of RSP on Madhesha issues and it was also the era that saw the formation of

various regional political parties based on Madhesha. After establishment MRMM,

various political parties, both armed and unarmed, came into the scene of Madheshi

politics because success of MRMM showed the possibility of ethnic identity

issues to be the centre of Nepalese politics. A section of the MRMM broke away

and formed an underground armed political party Janatantrik Terai Mukti Morcha

(JTMM) led by Goit which further split to form another JTMM led by Jwala Singh

(Mathema, 2011).

Madhesha Movement 2007

Following

the Jana Andolan II which carried promises of democratic reforms from

the Nepali state, the Madhesha based political parties and organizations

demanded for proportionate representation of Madheshi community in the governmental

bodies. To start with the proportionate representation, they wanted change in existing

constituencies and voting system in the to-be-held Constitution Assembly election.

But, failure of state to incorporate demands of Madhesha based political

parties and organizations in the interim constitution of Nepal agitated

Madhesha, finally developing into Madhesha Movement 2007.

Madhesha movement of 2007 can broadly be

divided into three phases. The first phase of Madhesha movement was led by

Nepal Sadbhawana Party (Aanandi Devi). The time before the promulgation of the

interim constitution characterize the period. The second phase of the movement

was lead by Madheshi Jana-Adhikar Forum (MJF), a Madheshi activist organization.

The time period between a day after the promulgation of interim constitution to

the first amendment of the constitution characterize the period. The third

phase of movement by led by United Democratic Madheshi Front[4] (UDMF) from February 13, 2008

to February 28, 2008.

The first phase of the Madhesha movement

started on 10 December 25, 2006 with the calling of Nepal Bandha by Nepal Sadbhawana Party (Aanandi Devi) to protest

against the provision of 205 constituencies in the interim constitution which

the party opposed (Sapkota & Singh, 2008). The party had demanded to

increase the number of constituency in Terai based on the population along with

the formation of constituency incorporating similar geography and culture; and the

demand for written provision, in interim constitution, for proportionate

representation of Madheshi in governmental bodies was also there (ibid.). Nepaljung

riot of December 10 and 11 is the major episode in the first phase of the

Madhesha movement which escalated and brought in the surface - the internal

tension that existed between Madheshi and Pahadhis, in the region. In the riot,

Madheshi chanted anti Pahadhis slongs and disturbed the business of Pahadhis

there and Pahadhis did the same for Madheshi whenever and wherever possible

(ibid.).

The second phase of the Madhesha

movement started with the arrest of MJF leaders on January 16, 2007 following

their act of burning copies of a day old interim constitution (Mathema, 2011,

25). Then, the activists of MJF in the Terai who demanded their leaders be

released called for a general strike throughout the Terai leading to Lahan

incident which killed 16-year-old Ramesh Kumar Mahato by a Maoist cadre named

Siyaram Thakur (Yadav, 2008). After the incident violent riots broke out in

Lahan spreading as far as Malangwa, Birjung, Biratnagar and many other parts of

Madhesha (Cheah, 2008). According to ICG (2007), Mahato’s killing was the spark

for prolonged agitation. Madheshi activists called for a general strike in the Terai

and organised widespread protests; the government responded with curfews and an

increased police presence (Cheah, 2008). Though figures are often disputed to

be under-reported, some 19 Madheshis were killed and another 500 wounded in

incidents leading up to the February 2, 2007 (ibid.). The second phase of

Madhesha Movement and arguably the most vital phase of the movement ended with

the second televised address of the Prime Minister in the name of nation where

the Prime Minister glorified the contribution the Madheshi communities had made

to Nepal and expressed his regret over the loss of lives during the protest

(Mathema, 2011, p.32).

The third phase of the Madhesh Movement

started in February 13, 2008 and lasted 16 days. The achievement of this

general strike was the eight-point agreement between the government of Nepal

and the UDMF; the eight-point agreement was not very different from the

22-point agreement between the government of Nepal and MJF (Mathema, 2011,

p.37).

Methodology

Although various research articles and

book has been published to describe and analyze the movement sociologically and

politically, no study has been done till now to describe how the main stream

media on Nepal approached and reported the movement. This study will fill the

same gap by studying how actually the main stream media of Nepal reported the

movement.

The study will comparatively analyze, using

content analysis, how the government owned main stream media and private owned main

stream media approached and reported the movement. Therefore, this study will

be both – qualitative and quantitative. Further, inductive reasoning technique

has been employed for the analysis and interpretation. For the study,

editorials of broadsheet dailies, Kantipur (KP) and Gorkhapatra (GP), published

in between 17 January, 2006 – 17 March, 2006 have been

taken as the study corpus. Only those editorials which have mentioned about Madhesha

Movement have come under the study.

The selection of editorial among various

news teams that are published in newspapers is because editorial is widely

accepted as the section where the newspapers are expected to voice their

opinion on the issues of national importance and interest. While, the selection

of KP and GP is purposive and is expected to be representative of private owned

media and government owned media respectively.

Data Presentation

Coverage of Madhesha Movement

In the span of three months, both KP and GP

published 38 editorials that were related to Madhesha movement. Out of the

total published editorials, 21 (55%) was published in GP while the remaining 17

(45%) was published in KP. On an average, KP published 6 editorials per month

relating to the Movement while the average number of editorials published per

month is 7 for the GP. If the last month of the study period, when no

editorials was published, is taken out of the equation than the average

editorials published by KP and GP during the Madhesha Movement rises to 9 and

11/month respectively.

Though GP has published more editorials on Madhesha

Movement as compared to KP, it was KP which for the first time published its

view on the Madhesha Movement. KP published its first editorial about the

movement following the general strike called by NSP (A) in 26 December, 2006

while GP published its first editorial two days later, only after the Nepalgunj

riot.

Coverage

of Madhesha Movement by Month

As

like the intensity of Madhesha Movement, the coverage about the movement was

maximum in the time period between 17 January - 17 February. This was second

phase of Madhesha Movement when the movement was at its peak. In this period of

one month, 11 (65%) and 17 (81%) editorials have been published in KP and GP

respectively. In total, 28 (76%) editorials were published in the period. Similarly,

KP has published 6 (35%) editorials in the period between 17 December -17

January but the editorial count for GP is 4 (19%) in the same period. This was

the period of first phase of Madhesha Movement when Madhesha Movement started

and was maturing. A total of 10 (26%) editorials have been published in between

the period by both KP and GP. In the last month of study, i.e. in the period

between 17 February and 17 March there are no editorials published about

Madhesha Movement because the Movement ended 7 February, 2007.

Views

about Madheshi Movement

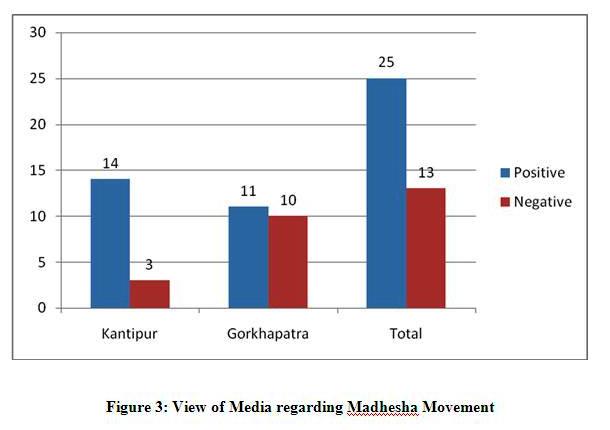

Editorials published in KP and GP

have presented Madhesha Movement in both negative and positive lights. Here,

the editorials which have, at least, acknowledged the demands of Madheshi

people during the Madhesha Movement have been kept under the ‘positive’

category and the editorials which have outright condemned the Madhesha Movement

as ‘unwanted’ are kept under the ‘negative’ category.

Of the total (17) editorials published in KP, 3

(21%) editorials have negative views about the Movement while 10 (48%)

editorials published in GP have negative views about the Movement, out of the

21 total editorials. Overall, 13 (34%) editorials have negative views about the

Movement to 25 (66%) which has positive views about the Movement.

Interpretation and Discussion

Both

KP and GP have given ample amount of importance to the Madhesha Movement which

is, respectively, shown by the average 9 and 11 editorials/month published by

them in the period of the Movement.

Uniform

Gorkhapatra

Though both of the newspapers have given importance

to Madheshi Movement, the importance given by the KP is different from that of

the GP. GP has expressed almost uniform views, in all of its editorials,

regarding the Madhesha Movement. It has throughout the Movement expressed

negative views about the ‘non-peaceful agitation’ of Madhesha and has presented

the Constitution Assembly (CA) election as the panacea of all the problems. GP

in its first editorial published in 28 December, 2006 following the Nepaljung

riot has urged peoples to put ‘national unity’ ahead of anything and

everything. GP has also expressed its dissatisfaction on the ‘regional and

ethnic politics’ done by NSP (A). Almost all the time, GP has suspected the

riots that occurred during the Movement as an act of ‘regressive force’ who

didn’t want the CA election and has reminded the agitating parties to be

careful about the misuse of the Movement by the regressive force at the time of

fragile transitional politics in Nepal. In the editorial published in 26

January, 2007, GP has asked all the people and political parties in the country

to concentrate on CA election rather than on the ‘small’ disputes of interim

constitution. Even when the Madhesha

Movement was at its peak it has not portrayed a positive picture regarding the

Movement but has respected the ‘demands’ of people in Madhesha. Likewise, condemning

the riots at different instances and places, GP has appealed the political

parties and organization involved in the Movement to protest in a peaceful way

and also urged them to sit in dialogue with government to meet their demands as

well as to solve their problem. Only towards the end of the Movement, when even

the government of Nepal was willing to respond to the demands of Madhesha, GP

has acknowledged the limitations of interim constitution and has lauded the

effort put in by the government to solve the issues of Madhesha. GP, even in

the editorial published by it following the second address of the Prime Minister

in the name of the nation, has not stopped claiming the involvement of

‘regressive force’ in the Madhesha Movement.

Dynamic

Kantipur

Although there is a striking similarity between the

views of KP and GP about the Madhesha Movement when it was still at its

incubation phase, KP has favored the Madheshi Movement from its fourth

editorial published on January 04, 2007. In the first three editorials

published by KP, it has voiced against the general strike called by NSP (A)

claiming strikes as a hindrance in the economic progress of the nation. KP in

its first editorials published about Madhesha Movement in 26 December, 2006 has

requested the organizers of general strike to find ‘creative’ ways to protest and

demand for their needs. In the same line, in the second and third article that

followed, KP has kept on expressing negative views about the Madhesha Movement.

Implicitly point out NSP (A), it has asked polities parties to make their

cadres calm and not take every of their grievances to road. Highlighting on the

need of ‘unity’ among Nepalese people, KP has explained, in its third editorial

of 29 December, 2006, Nepaljung riot of 27 December, 2006, as an ‘effort to

disintegrate’ the country and has asked security force to be alert in

maintaining peaceful environment. The third editorial of KP has also demanded

punishment for those who disturb communal harmony and peace.

But, KP seems to have completely changed its view regarding

Madhesha Movement from its fourth editorial and onwards. The fourth editorial,

shedding light on the problem of Madhesha and ethnic communities about the

first-past-the-post electoral system has favored the demands of ethnic and

marginalized communities for proportionate electoral system and proportionate

participation in the governmental bodies. It has also cautioned the political

parties to work on the demands of different organization and groups regarding

interim constitution and not promulgate the constitution till the differences

are worked out.

In the editorials that followed, KP has appealed the

government to incorporate the demands of Madhesha based political parties and

organization in the interim constitution. In its eighth editorial published on

19 January, 2007, KP has termed the burning of interim constitution as ‘not

illegal’ and has supported the demands of MJF. The same editorial has also

condemned the state for marginalizing Madhesha from the mainstream politics. Again

in the editorial that followed, KP has criticized the ‘excessive’ use of

security force which once it had advocated for, and has asked the problem of

Madhesha to solve politically rather by using security force.

In the thirteenth editorial published on 31 January,

2007, after the attack on journalists, KP has strongly opposed the violence

involved in the Movement and has explained the movement without entrance to

press as ‘non-peaceful’.

KP, in the editorials that it published after the

attack on journalists, has again supported the Madhesha Movement and also

stressed on the need of federalism, proportionate electoral system and

proportionate representation for the country. It has explained the first speech

of Prime Minister in the name of the nation as ‘insufficient’ and has condemned

the speech for keeping mum over the people killed and injured during the

Movement. Finally, in the last editorial published on 9 February, 2007, KP has

cautiously welcomed the second speech by the Prime Minister and also called the

Madhesha Movement as the movement of people but not an act of ‘regressive

force’.

Conclusion

Both KP and GP have given importance to Madhesha

Movement if frequency of editorials devoted for the Movement is taken into

consideration.

But the kind of importance given by KP

and GP to Madhesha Movement differs from each other. Coverage of GP about

Madhesha Movement has moved along the line of government of the particular time

characterizing itself to be a government media. Like the then government, the

GP can now be explained as an media which don’t match the popular notion ‘voice

of the voiceless’ given to media in general.

On the other hand KP can be called a

‘dynamic’ media which is quick to understand popular sentiment and report about

the events accordingly. The change in instance by KP from viewing the Madhesha

Movement from negative angle to positive positive angle is a testimony of its

ability to understand popular sentiment. But if overall dynamics of a newsroom

is to be analyzed, the change in instance of KP regarding Madhesha Movement

can’t be simply taken as adversarial[5] journalism, it can have many

political and economic implications behind it.

[1] There are 20 districts in Terai namely: Jhapa, Morang, Sunsari, Saptari, Siraha, Dhanusha, Mohattari, Sarlahi, Rautahat, Bara, Parsa, Chitwan, Nawalparasi, Rupandehi, Kapilavastu, Dang, Banke, Bardhiya, Kailali and Kanchanpur (Simkhada, 2063).

[2] Nepal Sadbhawana Parisad was later changed in to a political party named Nepal Sadbhawana Party after restoration of democracy in 1990 (Mathema, 2011).

[3] Maoists to win the support of the marginalized communities established various central-level ethnic fronts following the Supreme Court decision of 1999 to ban languages other than Nepali in government offices (Mathema, 2011).

[4] Alliance between Rajendra Mahato-led Sadhvawana Party, MJF and Terai Madhesh Loktantrik Party (TMLP) (Mathema, 2011).

[5] A form of journalism which critically reports about the actions of state.

Reference

CBS. (2012). National population and housing census 2011.

Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics.

Shah, S.G. (n.d.). Peaceful resolution of

ethno-political movement in Nepal Madhesha. Retrieved on 15 December, 2012

from http://cpjsnepal.org/pdf/feature_shree_govind.pdf

Yadav,

R.R. (2008). Madhesha bidhrohama Siraha-Saptari, 75-102. In Bhaskhar Gautam

(ed.) Madhesha bidrohako nalibeli. Kathmandu: Martin Chautari.

Sapkota,

S. and Singh, S. (2008). Apratyasit nepaljung danga, 60-73. In Bhaskhar Gautam

(ed.) Madhesha bidrohako nalibeli. Kathmandu: Martin Chautari.

Mathema, K. B. (2011). Madheshi uprising: The resurgence

of ethnicity. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point.

Rimal,

G.N. (2009). Infused ethnicities: Nepal’s interlaced and indivisible social

mosaic. Kathmandu: Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-Nepal.

Simkhada,

D. (2063). Madheshi andolan ra musalman samudaya. Baha Jornal, 3 (3),

29-44.

Cheah,

F. (2008). Inclusive democracy for madheshis: The quest for identity, rights

and representation. Retrieved on 18 December, 2012, from http://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/Attachments/ResearchAttachment/Report%20-%20Farah.pdf

ICG.

(2007). Nepal’s troubled Terai region. Retrieved on 15 December, 2012, from http://un.org.np/sites/default/files/report/tid_105/2007-07-14-nepal_s_troubled_Terai_region.pdf

APPENDIX – I: Chronology of Key Madhesha

Events

1951: Nepal Terai Congress formed under Vedanand

Jha.

1952: First Citizenship Act introduced.

1957: Imposition of Nepali as sole language for

education sparks protests in Terai.

1959: NC sweeps first democratic elections; Nepal Terai

Congress wins no seats.

1964: New Citizenship Act based on 1962 Panchayat

constitution makes it harder for Madheshis to acquire citizenship.

1979: King Birendra holds referendum on Panchayat

system; higher support for multi-party democracy in Terai districts.

1983: Nepal Sadbhavana Parishad formed under

Gajendra Narayan Singh to raise Madheshi issues.

1990: People’s movement brings Panchayat system to

an end. New constitution promulgated. Nepal Sadbhavana Parishad registers as

party to contest elections but demands constituent assembly.

1994: Government sets up Dhanapati Commission on

citizenship issue.

1996: Maoists launch insurgency.

1997: Madheshi Janadhikar Forum (MJF) established in

Biratnagar as cross-party intellectual platform.

2000: Maoists set up Madheshi Rashtriya Mukti Morcha

(MRMM) under Jai Krishna Goit in Siliguri.

2004: Matrika Yadav appointed as head of MRMM; Goit

splits and forms the Janatantrik Terai Mukti Morcha (JTMM).

2006

24 April: Following nineteen-day mass movement, king

announces reinstatement of parliament.

18 May: Parliamentary proclamation curtails royal

powers and declares Nepal a secular state; Hindu organizations, especially in

the Terai, protest.

17 July: Matrika Yadav announces war against JTMM.

August-October: Jwala Singh expelled from JTMM forms

his own faction. Frequent JTMM strikes (both factions) affect normal life in Terai.

Increase in clashes between Maoist-JTMM and JTMM factions.

23 September: JTMM (G) activists shoot dead Rastriya

Prajatantra Party (RPP) Member of Parliament (MP) Krishna Charan Shrestha in

Siraha.

22 October: JTMM (G) expresses willingness to talk;

government agrees in principle (26 October) but makes no move for negotiations.

26 November: Citizenship law amended enabling Madheshis

to get citizenship certificates and associated rights.

16 December: NSP (A) protests interim constitution

provisions on electoral system and its silence on federalism. JTMM (JS) imposes

prohibition on non-Madheshis driving on Terai roads for a fortnight.

26 December: NSP (A) protest turns violent in Nepalgunj;

communal aspects with Pahadhi-Madheshi clashes, while police accused of anti-Madheshi

bias. Government forms commission to investigate (27 December).

30 December: Prime Minister Koirala expresses his

willingness to solve Terai problem through talks. Ian Martin, special

representative of the UN Secretary-General, voices concern about violent

activities in eastern Terai.

2007

6 January: JTMM (JS) expresses willingness to talk

to government under UN auspices.

12 January: Three-day Terai strike called by JTMM (G).

Nepal’s Troubled Terai Region

16 January: MJF announces strike in Terai to protest

interim constitution’s promulgation. Its leaders are arrested while burning

copies of the statute in Kathmandu.

19 January: Maoists clash with MJF activists in

Lahan, killing student Ramesh Kumar Mahato.

20 January: Maoist cadres seize and cremate Mahato’s

body; Lahan put under curfew.

21 January-7 February: Movement picks up across

eastern Terai against the government and Maoists, with growing public support,

mass defiance of curfews, clashes between police and protestors, attacks on

government offices and almost 40 people killed. Maoists accuse feudal elements

and royalists of inciting unrest and reject talks.

29 January: NSP (A) minister Hridayesh Tripathi

resigns from government. Government arrests former royal ministers on charges

of instigating violence.

31 January: Prime Minister Koirala makes national

television address appealing for dialogue; protestors reject the offer.

2 February: Government forms committee led by Mahant

Thakur to talk to all agitating groups.

7 February: Koirala makes second address; government

agrees to introduce federalism and allot half the seats in the constituent

assembly to Terai.

8 February: MJF cautiously welcomes Koirala’s

address, suspends agitation for ten days and sets preconditions for talks: home

minister’s resignation, declaration of all those killed as martyrs and a Madheshi-led,

independent panel to investigate atrocities.

11 February: Madheshi MPs demand immediate amendment

of interim constitution.

13 February: JTMM (JS) agrees to talk and halt

violence. JTMM (G) rejects talks offer (14 February).

15 February: Home Minister Sitaula apologizes for

mistakes during Terai unrest but refuses to quit.

19 February: MFJ renews its agitation, saying

government failed to create environment for talks. JTMM (G) calls three-day Terai

shutdown (21 February).

22 February: Thakur committee asks government to

withdraw all charges against JTMM factions to create environment for

talks.

1 March: Madheshi Tigers abduct eleven people from

Saptari.

4 March: JTMM (JS) resumes armed revolt, accusing

government of not wanting negotiations.

6 March: NSP (A) threatens to leave SPA if interim

constitution is not amended.

9 March: Legislature amends interim constitution

creating Electoral Constituency Delimitation Commission (ECDC) to revise

constituencies and guaranteeing federalism.

21 March: MJF-Maoist clash in Gaur, killing 27 Maoists

and leaving dozens injured. Curfew imposed.

Government forms panel to investigate and submit

report in fifteen days (23 March). MJF protests banned in Rautahat, Siraha,

Jhapa and Morang (24 March).

11 April: Peace and Reconstruction Minister Ram

Chandra Poudel calls MJF and JTMM for talks.

18 April: Madheshi MPs reject ECDC recommendations,

demand fresh census and block functioning of interim legislature for over a

month.

20 April: OHCHR investigation holds law enforcement

agencies, MJF and Maoists jointly responsible for Gaur massacre.

26 April: MJF applies to the Election Commission to

register as a political party.

10 May: Ram Chandra Poudel meets MJF president

Upendra Yadav in Birgunj.

13 May: JTMM (G) kills JTMM (JS) district

chairman of Rautahat. JTMM (JS)

retaliates by killing two JTMM (G) activists.

25 May: Cabinet forms commission to investigate

killings during the Terai unrest.

1 June: Government-MJF talks in Janakpur; MJF

presents 26 demands. Nepal’s Troubled Terai Region

8 June: NSP factions merge under banner of Nepal

Sadbhavana Party (Anandidevi).

13 June: Two Maoists killed in clash with MJF in

Rupandehi.

22 June: MRMM central committee dissolved after

differences between Matrika Yadav and Prabhu Sah.

Ram Kumari Yadav appointed coordinator of new ad-hoc

committee; Prachanda takes charge of the party’s eastern Terai region.

24 June: Government announces 22 November date for

constituent assembly elections; extends ECDC term by 21 days so it can review

its earlier report.

2 comments:

Informative. Thank you. And at a moment of crisis your reference helps. Thank you.

can u email me the citation of 1951: Nepal Terai Congress formed under Vedanand Jha.

Post a Comment